Taking up our discussion of Trinity and mystery from Karen Kilby, I came across a similar discussion in Hilary of Poitiers (300-368). He is here, in On the Trinity, discussing how it is that the Son is eternally born from the Father–a basic confession of Christian faith:

Taking up our discussion of Trinity and mystery from Karen Kilby, I came across a similar discussion in Hilary of Poitiers (300-368). He is here, in On the Trinity, discussing how it is that the Son is eternally born from the Father–a basic confession of Christian faith:

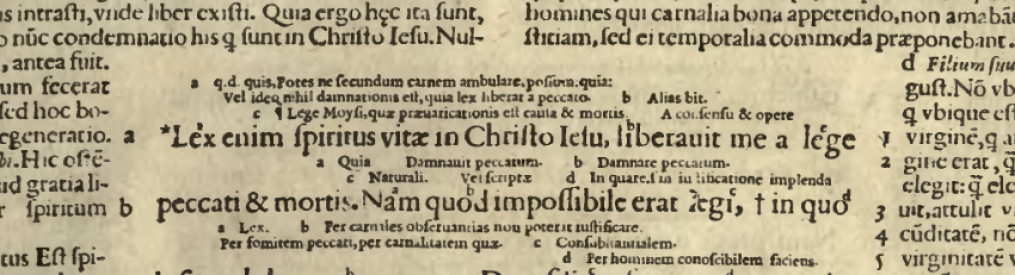

Penetrate into the mystery, plunge into the darkness which shrouds that birth, where you will be alone with God the Unbegotten and God the Only-begotten. Make your start, continue, persevere. I know that you will not reach the goal, but I shall rejoice at your progress. For he who devoutly treads an endless road, though he reach no conclusion, will profit by his exertions. Reason will fail for want of words, but when it comes to a stand it will be the better for the effort made. (On the Trinity, Book II, §10; in Gunton, ed., The Practice of Theology, 229)

Hilary seems to be setting out on a quite different path than Karen Kilby in her recent article, “Is An Apophatic Trinitarianism Possible?” Making a comparison across disciplines, she argues, “[T]heology does not ‘progress’ in the way that mathematics does, and the doctrine of the Trinity which is the conclusion of a long hermeneutical struggle should not itself be taken as a fresh starting point for a new enquiry” (70). For Kilby, “[T]here ought properly to be … a resistance to, a fundamental reticence and reserve surrounding, speculation on the Trinity” (72).

The proper grammar surrounding the Trinity has been achieved: this is the result of great struggle in the first five centuries of the Church’s life. But that does not mean that we may now set off, as it were, from the Trinitarian definitions as a launching pad to deeper things. Instead, the Trinity remains most properly shrouded in a veil of apophasis. But Kilby makes an important additional distinction: apophasis is not simply a sheer act of denial–that we, for instance, have no knowledge whatsoever about the Trinity. Rather, the Trinity is so overwhelmingly excessive that all our attempts to “understand” what the Trinity is like fall short.

The Trinitarian dogmas, Kilby wishes to affirm however, do really teach us things about the nature of God’s life, even the immanent life of Father, Son and Spirit together. They also, importantly, hedge off certain wrong understandings. In her own words, “Or again, one thing the doctrine affirms is that there really is only one God, and to say this is to say something about the immanent Trinity, but this does not mean that one has a comprehension of – or even a feeling for – how the oneness of God fits with the threeness” (71). And here Kilby is much closer to Hilary:

Therefore, since no one knows the Father save the Son, let our thoughts of the Father be at one with the thoughts of the Son, the only faithful Witness, who reveals him to us. It is easier for me to feel this concerning the Father than to say it… We must feel that he is invisible, incomprehensible, eternal. But to say [these things]… all this is an acknowledgement of his glory, a hint of our meaning, a sketch of our thoughts, but speech is powerless to tell us what God is, words cannot express the reality. (§7; in Gunton, 227-228)

So what purpose, then, does theological writing on the Trinity serve? Karen Kilby and Hilary of Poitiers here offer the same answer:

So much I have resolved to say concerning the nature of their Divinity not imagining that I have succeeded in making a summary of the faith, but recognising that the theme is inexhaustible. So faith, you object, has no service to render, since there is nothing that it can comprehend. Not so; the proper service of faith is to grasp and confess the truth that it is incompetent to comprehend its object. (Hilary, §11; in Gunton, 229-230)

With equal elegance, Kilby: “What answers we may appear to have – answers drawing on notions of processions, relations, perichoresis – would be acknowledged as in fact no more than technical ways of articulating our inability to know” (67). Perhaps this, then, is progress: a recognition of the fundamental–indeed, theologically reasoned–need for a “trinitarian theological modesty” (67), or what Sarah Coakley calls “a theology committed to ascetic transformation.” Indeed, in the last analysis, “To know God is unlike any other knowledge; indeed, it is more truly to be known, and so transformed” (Is There a Future for Gender and Theology?, 5).